Barandiaran, X. E., & Pérez-Verdugo, M. (2025). Generative midtended cognition and Artificial Intelligence: Thinging with thinging things. Synthese, 205(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-025-04961-4

Previous preprint available:

- Barandiaran, X. E., & Pérez-Verdugo, M. (2024). Generative midtended cognition and Artificial Intelligence. Thinging with thinging things (arXiv:2411.06812). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.06812

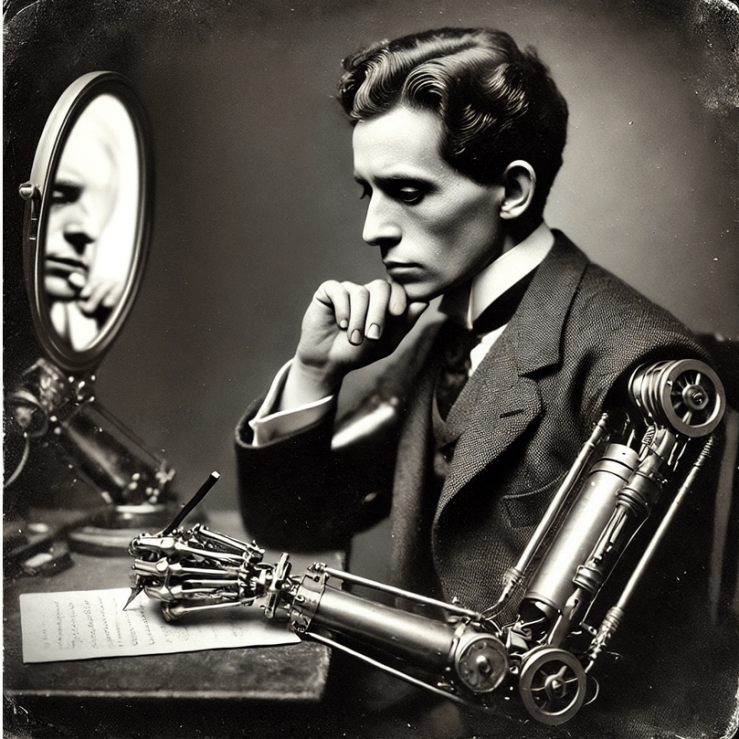

I really do think with my pen, because my head

often knows nothing about what my hand is writing

WITTGENSTEIN

I’m excited to share a recent publication co-authored with Marta Pérez-Verdugo titled Generative Midtended Cognition and Artificial Intelligence: Thinging with Thinging Things. This paper represents an initial step in our broader exploration of how generative AI transforms human cognitive agency in ways that traditional frameworks of extended cognition fall short of capturing.

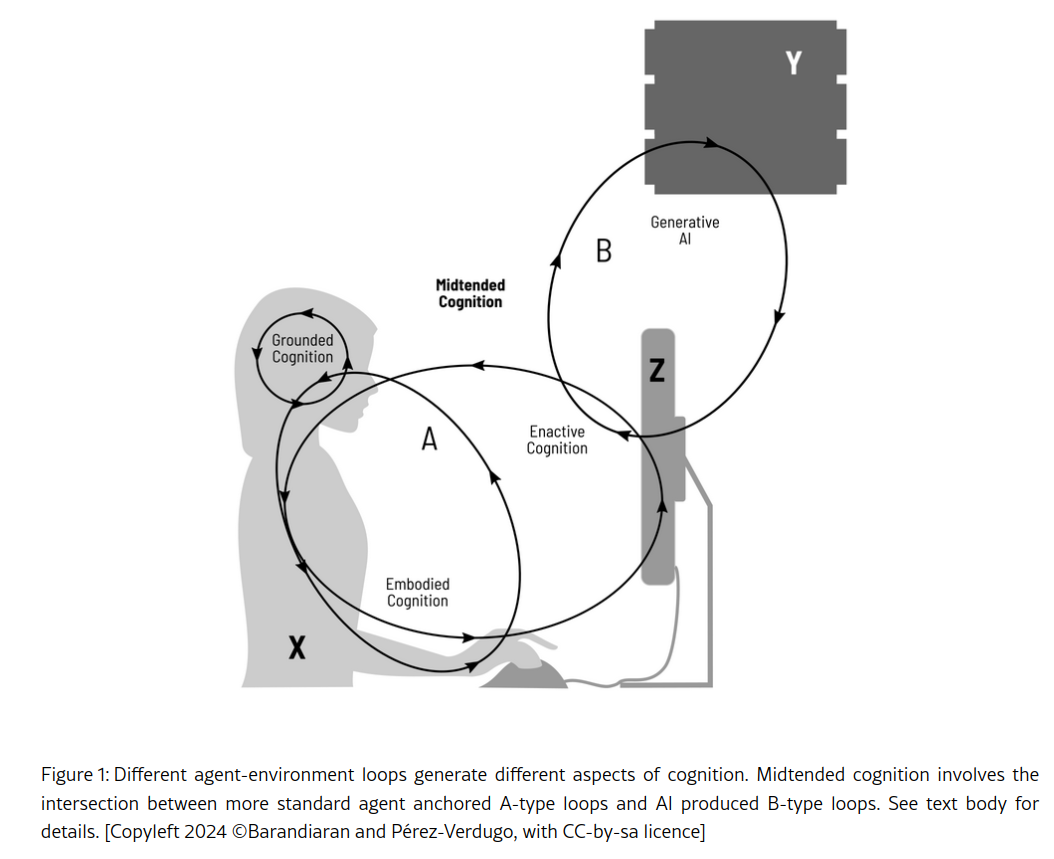

Did you ever experience the situation in which a human provided you with the word you were struggling to find out, accepted the suggestion, made it your own, and kept talking? Well, it happens that generative AI technologies are expanding this phenomenon to unprecedented levels. In this paper we start thinking about the consequences. To do so our work introduces the novel concept of «generative midtended cognition.» This term describes a hybrid cognitive process where generative AI becomes part of human creative agency, enabling interactions that sit between intention and extension: thus midtention. With AI’s ability to iteratively generate complex outputs, «midtended» cognition reflects the creative process where humans and AI co-generate a product, shaping the outcome together (see figure below). We explicitly define midtended cognition as follows:

Given a cognitive agent X, a generative system Y (artificial or otherwise) and cognitive product Z, midtension takes place when generative interventions produced by Y become constitutive of the intentional generation of Z by X, whereby X keeps some sense of agency or authorship over Z.

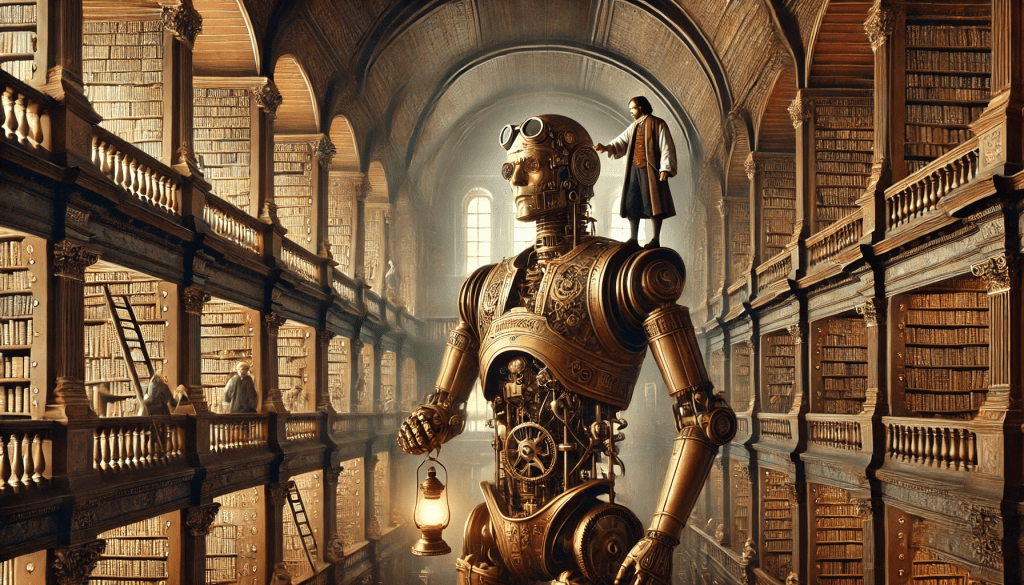

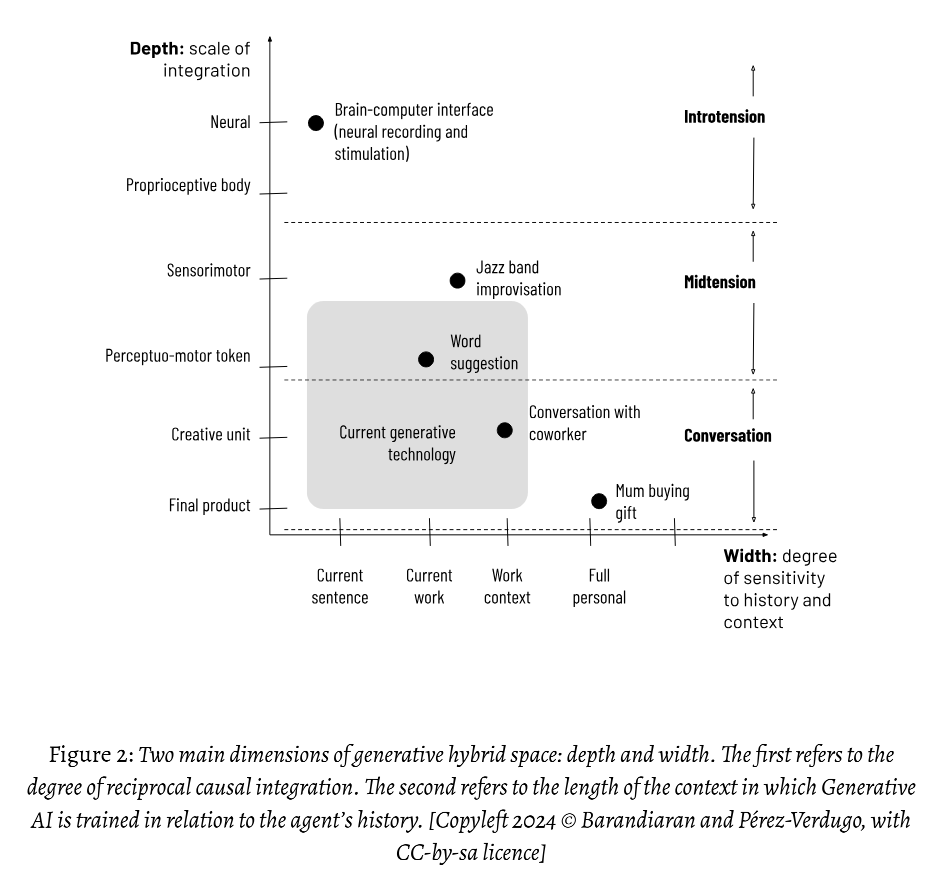

For those interested in cognitive science, philosophy of mind, or the implications of generative AI, this paper offers a theoretical basis to understand the cognitive depth of these human-AI interactions. Beyond classical extended, enactive and material cognition approaches, we suggest that generative AI initiates a form of cognition closer to social interactions than classical extended cognition approaches to technology. Yet, interacting with a generative AI is not itself a social interaction stricto sensu. It is something new. In order to get a better grasp on this novelty, we introduce and analyse two dimensions of “width” (sensitivity to context) and “depth” (granularity of interaction).

Given the unique generative power of these technologies and the hybrid forms of human-environment interactions they make possible, it’s essential to address both the promising potential and the ethical challenges they introduce. The paper explores multiple scenarios, from authenticity risks to the spectre of cognitive atrophy. But perhaps, it points out to a new concept we find particularly revealing and worth a follow-up paper to develop in depth: that of the economy of intention. We have previously analysed the concept of the economy of attention, an economic driver of contemporary social order and disorders. The phenomenon of Midtended Cognition might well move cognitive capitalism a step forward into a deeper commodification of the mind: not only the information that captures our attention, but the very intentional plans, creations, and projects we make «our own» might now be vulnerable to corporate injection.

ABSTRACT: This paper introduces the concept of “generative midtended cognition”, that explores the integration of generative AI technologies with human cognitive processes. The term «generative» reflects AI’s ability to iteratively produce structured outputs, while «midtended» captures the potential hybrid (human-AI) nature of the process. It stands between traditional conceptions of intended creation, understood as steered or directed from within, and extended processes that bring exo-biological processes into the creative process. We examine the working of current generative technologies (based on multimodal transformer architectures typical of large language models like ChatGPT), to explain how they can transform human cognitive agency beyond what the conceptual resources of standard theories of extended cognition can capture. We suggest that the type of cognitive activity typical of the coupling between a human and generative technologies is closer (but not equivalent) to social cognition than to classical extended cognitive paradigms. Yet, it deserves a specific treatment. We provide an explicit definition of generative midtended cognition in which we treat interventions by AI systems as constitutive of the agent’s intentional creative processes. Furthermore, we distinguish two dimensions of generative hybrid creativity: 1. Width: captures the sensitivity of the context of the generative process (from the single letter to the whole historical and surrounding data), 2. Depth: captures the granularity of iteration loops involved in the process. Generative midtended cognition stands in the middle depth between conversational forms of cognition in which complete utterances or creative units are exchanged, and micro-cognitive (e.g. neural) subpersonal processes. Finally, the paper discusses the potential risks and benefits of widespread generative AI adoption, including the challenges of authenticity, generative power asymmetry, and creative boost or atrophy.